Across continents, billionaires quietly buy vast tracts of land – farmland, ranches, and remote retreats – reshaping who controls Earth’s most essential resource. From the U.S. heartland to New Zealand valleys, ultra‑wealthy investors are acquiring land like never before.

This trend is often framed as a financially prudent move, an inflation hedge, or strategic diversification. Yet it’s also driven by anxieties around economic instability, pandemics, and social unrest, amplifying demand for privacy, security, and even apocalypse-prepared shelters among the global elite.

From Fringe to Fashionable

What was once fringe survivalist territory is now mainstream among Silicon Valley billionaires. LinkedIn cofounder Reid Hoffman noted that over half of his peers have secured some form of apocalypse insurance, such as underground bunkers or escape retreats.

These preparations have become status symbols … luxury shelters with gyms, cinemas, pools, and long‑term supplies. The shift reflects fears of global collapse and the extraordinary resources available to the ultra‑rich.

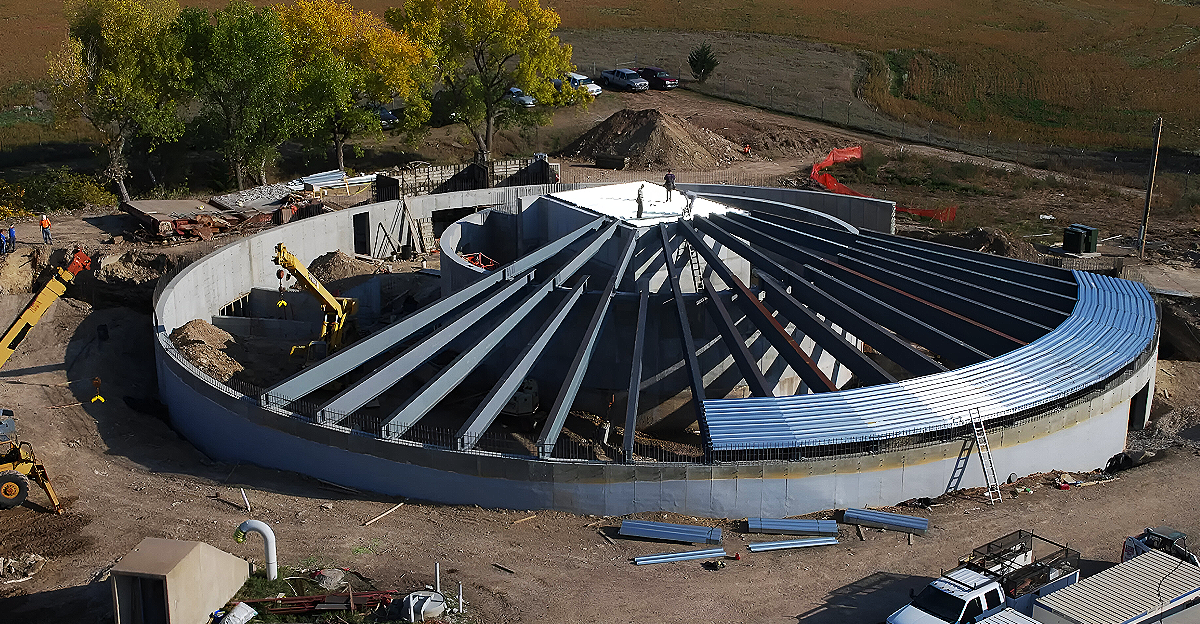

The Rise of Billionaire Bunkers

Luxury bunkers are far removed from Cold War fallout shelters. Today’s underground compounds blend comfort and survival planning, offering recreation areas, climate-controlled interiors, and food and water storage for months.

Companies that build high-end bunkers report steep demand growth as pandemic-era fears intensified. The world’s richest now expect safety and luxury to coexist, investing heavily in fortified retreats.

Safety, Stability, Space

New Zealand’s isolation, political calm, and robust infrastructure make it a beacon for wealthy foreigners seeking refuge. The Guardian Week reported that Peter Thiel, among others, has described it as nearly utopian and has invested heavily there.

Silicon Valley financiers often view New Zealand property purchases as a discreet way to signal doomsday readiness. Meanwhile, remote locations in the U.S. – from the Pacific Northwest to parts of the Mountain West – are valued for privacy, open land, and distance from urban centers.

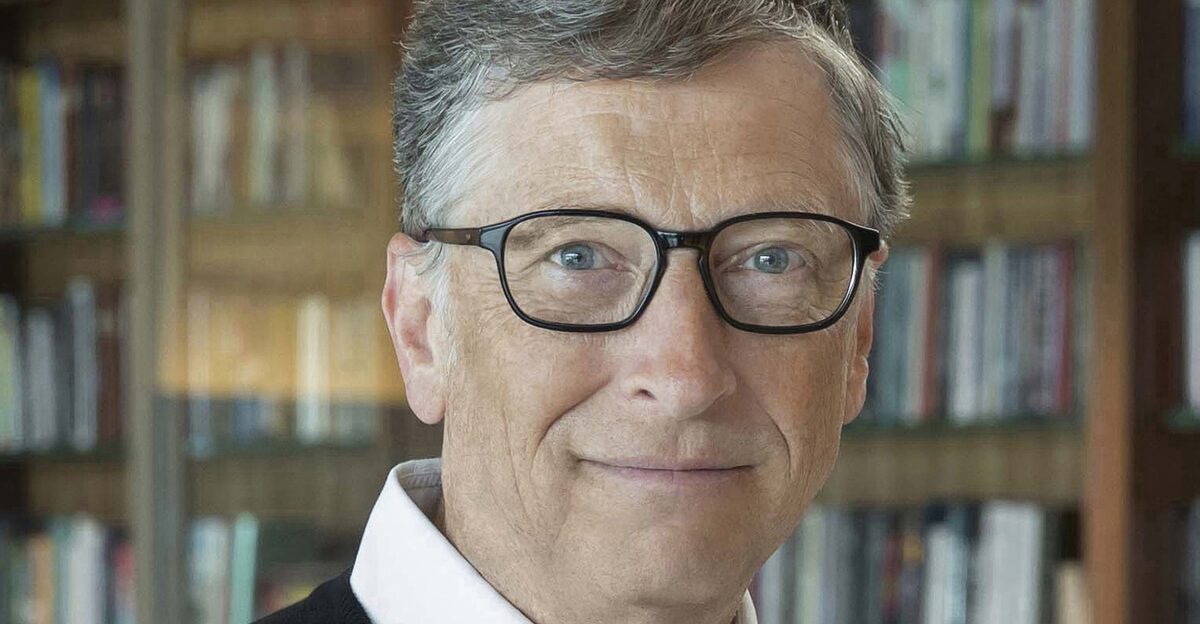

Bill Gates – America’s Farmland Baron

Bill Gates is widely recognized as America’s largest private farmland owner. His holdings span roughly 242,000–275,000 acres across nearly 20 states, including large tracts in Louisiana, Arkansas, Nebraska, and Arizona.

Managed via Cascade Investment and related entities, these acquisitions mark an investment strategy grounded in stability and long‑term value. Though substantial, Gates’ land represents under 0.03% of total U.S. farmland.

Global Billionaire Land Holdings Beyond the U.S.

This trend reaches far beyond U.S. borders. Ray Dalio holds over 500,000 acres in Australia, and, according to Investopedia, figures like Ted Turner, Aliko Dangote, and others have purchased massive tracts for conservation, agriculture, and retreats.

With growing interests in wealthy high-income regions and resource-rich, lower‑income countries, billionaire demand pushes global land prices upward, influencing ownership patterns worldwide.

Land as the Ultimate Safe Asset

Land is a tangible, real-world asset, a hedge against financial volatility and inflation. While stocks and bonds fluctuate, land historically appreciates steadily. For billionaires, investing in land is not only a status symbol or lifestyle choice, but also a strategic buffer against economic crises.

In prized regions, land rarely depreciates, making it a cornerstone in ultra‑wealth portfolios.

Farmland and Food Security Motivations

A considerable share of billionaire-held land is agricultural. Gates’ holdings cover potato, soy, and vegetable acreage, including 14,500 acres in Washington’s Horse Heaven Hills, used for McDonald’s supplies. Proponents argue these holdings support food security and sustainable farming.

Critics counter that massive private ownership can monopolize farmland access, inflating food prices and creating barriers for small producers.

Corporate Ownership and Housing Market Pressures

While farmland captures headlines, billionaire and corporate acquisitions also shape urban landscapes. Investment firms now own vast rental portfolios, often displacing lower and middle-income households. These entities drive up housing costs and rent, contributing to gentrification and eviction spikes.

In some cities, investor‑owned vacant units outnumber unsheltered people, raising questions about housing equity and market imbalance.

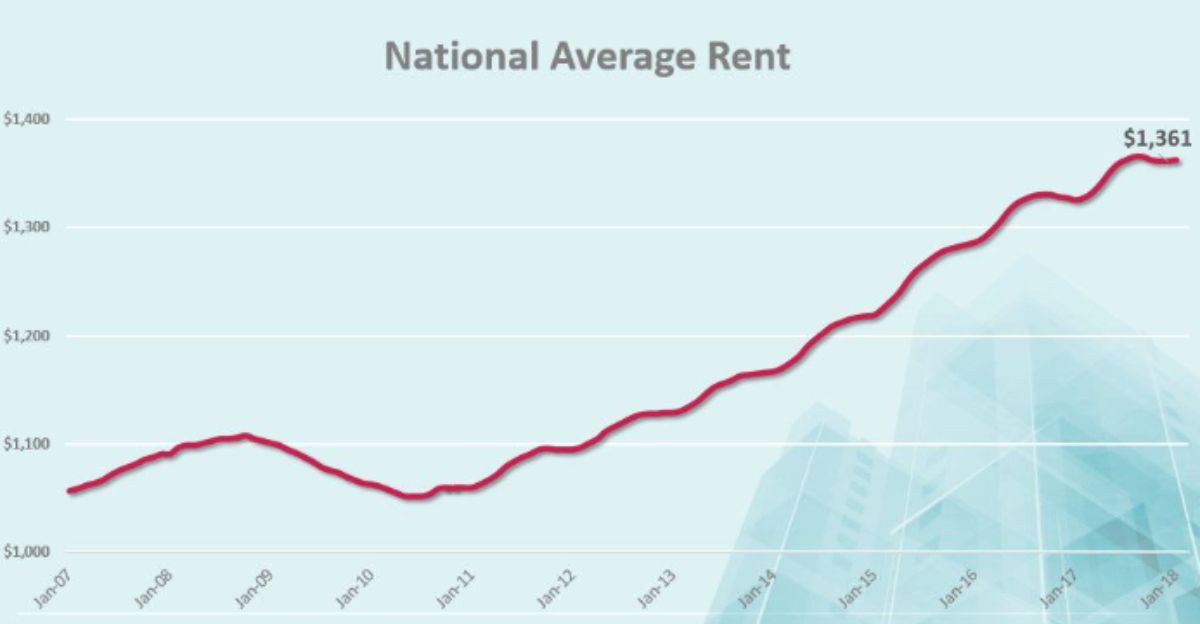

Price Escalation Under Concentrated Ownership

Large-scale cash buyers often outbid residents, driving up land and housing prices. In the UK, decreasing homeownership rates – the lowest since the 1980s – are linked to speculative land holdings by wealthy investors.

Similar patterns emerge in other major markets, where concentrated ownership reduces affordability and limits opportunities for first‑time buyers and families.

Displacement and Community Erosion

Rapid land consolidation forces communities to make tough choices: sell, rent, or relocate. Residents find themselves priced out across rural Nebraska, Cornwall, and elsewhere as local land shifts hands.

In the U.S., about 16 million homes are vacant even as homelessness rises, an uneasy paradox where excess and deprivation coexist.

Rural Governance and Local Disempowerment

Ownership through opaque trusts and shell companies can undermine local land governance. When absentee billionaires hold large parcels, land use and infrastructure decisions may be made without community input.

This distance weakens local engagement and can stall investments in roads, schools, or shared resources essential to rural residents.

Institutional Control and Policy Influence

Much land is held not by individuals but by corporations and funds controlled by ultra‑wealthy interests. Private equity firms dominate rental markets and affordable housing sectors, pushing rent increases and evictions.

Critics argue these developments worsen economic and racial inequality, transforming housing from a public need into a commodity for profit.

Secrecy Surrounding True Ownership

The Pandora Papers and other exposés reveal that many billionaire land acquisitions are obscured through offshore trusts and LLCs.

While legal, these structures reduce transparency, making it difficult for governments and the public to trace ownership or tax obligations and raising concerns about regulatory oversight and accountability.

Mixed Environmental and Social Impact

Some billionaire-owned lands are used for conservation projects or renewable energy installations. Yet others limit public access or support controversial developments.

In Australia, legal disputes, such as those involving Mike Cannon‑Brookes, highlight friction when large‑scale projects face local environmental and social opposition.

Inequality Intensified by Asset Concentration

Concentrated land ownership drives wealth inequality, as rising land values enrich a small minority while leaving many without secure tenure or access to affordable housing.

The widening gap between asset‑rich elites and marginal communities deepens social and economic divides, especially in agricultural regions and cities with tight land markets.

Billionaire Justifications and Criticism

Some financiers frame land ownership as visionary, backing conservation trusts, climate technology, or philanthropic initiatives. Others treat land primarily as high-return investments.

This dichotomy prompts debate: Should billionaire land holdings serve broader public goals, or is private ownership enough? Policymakers and the public are increasingly scrutinizing these practices.

Emerging Policy Responses

Lawmakers are exploring tools to counter concentrated land ownership. Proposals include land‑use transparency laws, land‑bank creation, foreign or absentee ownership limits, and tenant protections.

Jurisdictions across the U.S., UK, and Europe are debating reforms – though legal, economic, and political challenges continue to stall broad change.

Personal Impacts on Real People

The effects are tangible on the ground. Rising rents displace long-term residents, and farmers cannot compete with cash-rich bidders.

In parts of rural Nebraska and Cornwall, small communities see local stewardship replaced by absentee investment logic, permanently altering the social fabric and regional identity.

The Crossroads Ahead

Billionaire landownership is reshaping society, from rural governance to global housing affordability. The pressing question is: Will land remain a commodity of the wealthy or become a communal foundation for opportunity?

The outcome hinges on policy balance, public engagement, and whether communities reclaim land’s potential as a shared resource rather than a private stronghold.