Deep beneath the ocean’s surface lie ecosystems, geological formations, and biological hotspots that scientists are only beginning to understand.

From Arctic hydrothermal vents to Greenland’s unexpected coral gardens, these seven underwater discoveries reveal how much of our planet remains unexplored.

Each location challenges what we thought we knew about ocean life, geology, and the hidden architecture of Earth’s seafloor. Over the following slides, discover the places that the world hardly talks about, what makes these places so scientifically remarkable, and why they matter.

1. Gakkel Ridge

Stretching nearly 1,300 miles between Greenland and Siberia, the Gakkel Ridge is the world’s largest mid-ocean ridge and one of the most isolated.

It plunges to depths exceeding three miles, making exploration extraordinarily difficult. In 2003, scientists made a groundbreaking discovery: the first hydrothermal vents ever confirmed in Arctic waters.

These mineral-rich vents became instant hotspots for dense microbial and animal life in a region thought to be largely barren.

2. Von Damm Vent Field

Located along the mid-ocean ridge system within the Caribbean Sea, Von Damm Vent Field is one of the most biologically productive underwater features on Earth.

Rising 246 feet from the seafloor, this structure is uniquely composed of talc and magnesium silicate—a rare mineral combination for hydrothermal vents.

The vent field transfers approximately 500 megawatts of energy into surrounding waters, making it a natural supercharger for marine life.

3. Cenotes of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula

Cenotes are natural sinkholes formed when the limestone bedrock collapses, revealing freshwater and saltwater caverns below. The Yucatán Peninsula is home to thousands of underwater cenotes, many of which remain unexplored.

Scientists believe that many were created by the Chicxulub impact event millions of years ago, when an asteroid or comet struck Earth, causing widespread damage to the landscape. These sinkholes have become windows into underground ecosystems and ancient geological history.

4. Silfra Fissure

In Iceland, Silfra Fissure offers a unique geological privilege: the chance to swim between two continental plates. Here, the Eurasian and North American plates meet and continuously drift apart, creating a dramatic 206-foot deep crevice filled with crystalline water.

The fissure grows by 0.78 inches annually, making it a living laboratory of plate tectonics. The water is so clear it’s been called “the clearest water on Earth.”

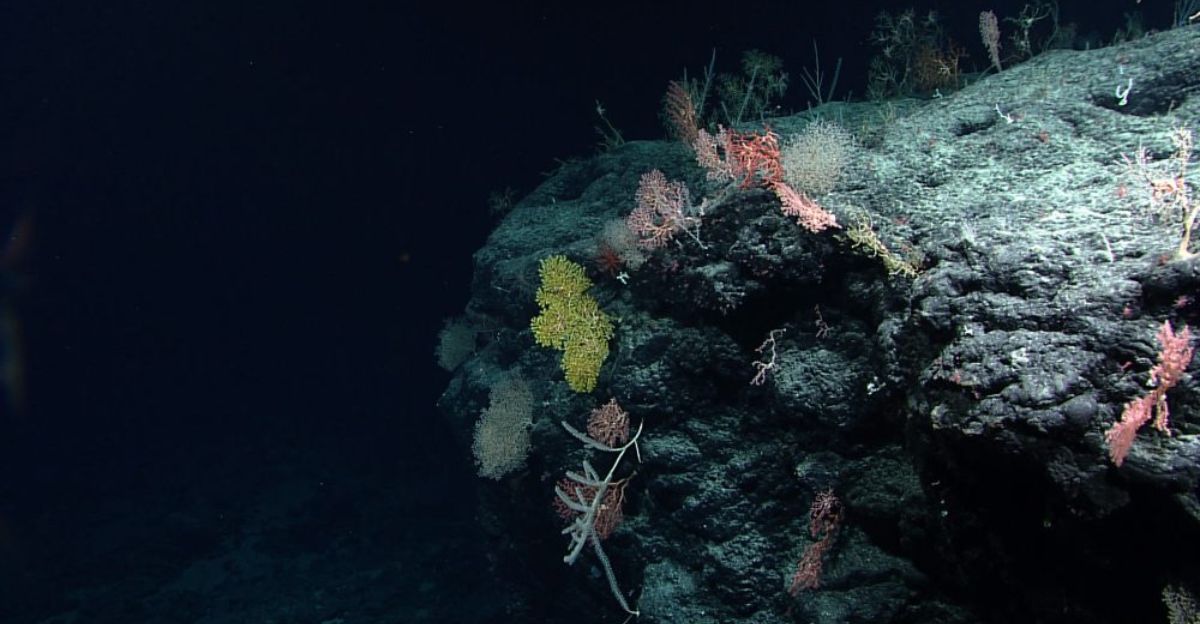

5. Carter Seamount

Seamounts are underwater mountains formed by extinct volcanoes, and thousands lie undiscovered beneath the ocean.

Carter Seamount, rising to 200 meters below the Atlantic Ocean’s surface, is one of the rare exceptions: it was thoroughly studied by researchers from the University of Bristol in 2013.

The seamount hosts diverse marine ecosystems, including sponges, coral reefs, and specialized species adapted to deep-sea conditions.

With over one million submerged volcanoes estimated worldwide, Carter represents just a fraction of unexplored seafloor ecosystems.

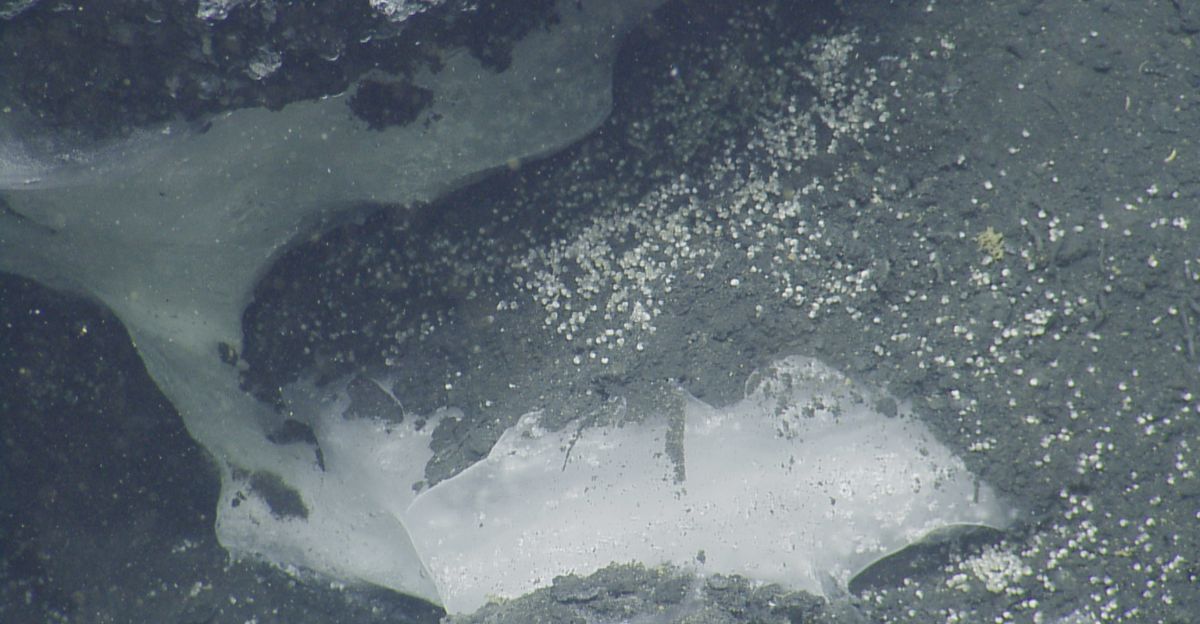

6. Champagne Seeps on the Cascadia Margin

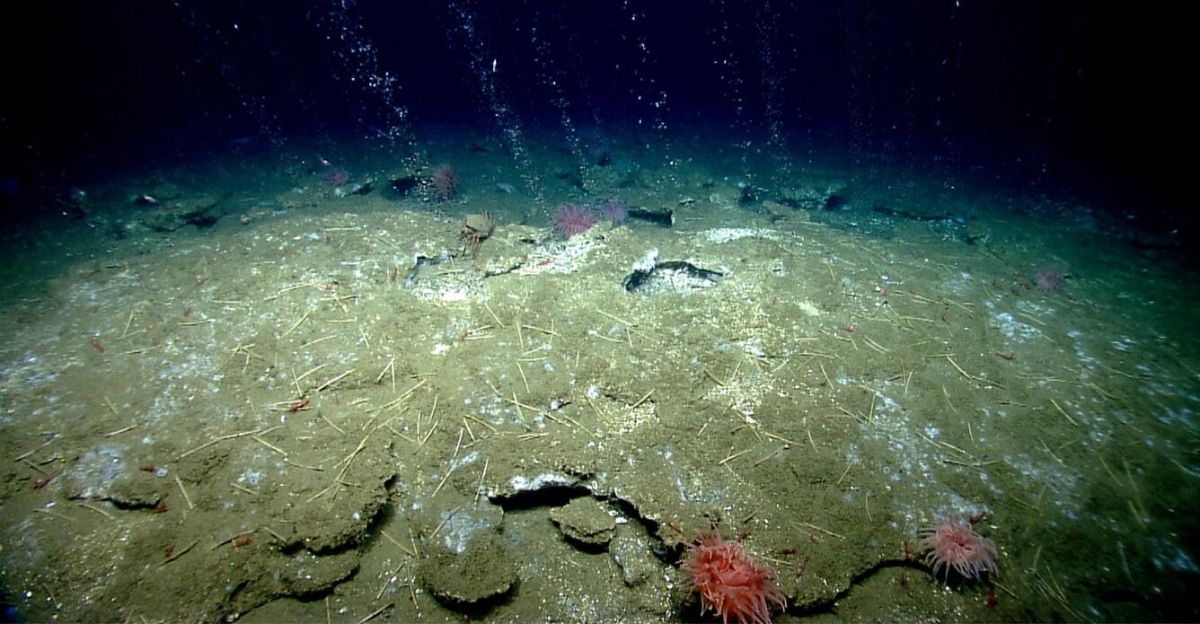

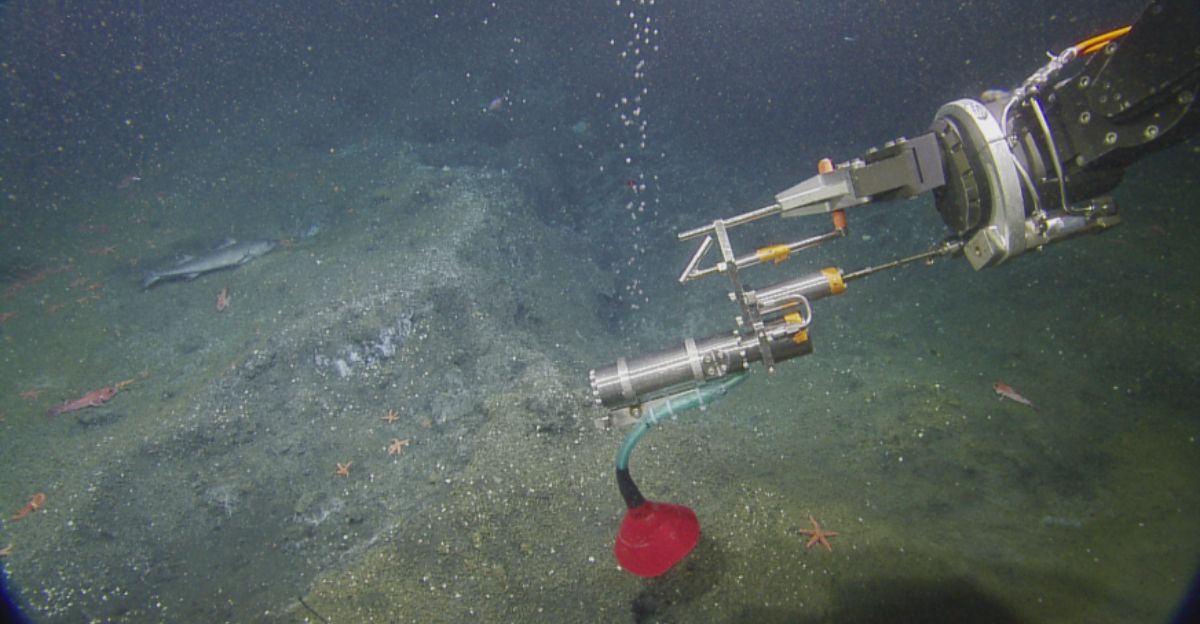

Along the Cascadia Margin off the U.S. West Coast, cracks in the seafloor release methane gas in a spectacular display.

Called “champagne seeps” because the methane fizzes upward like carbonated bubbles, these cold seeps create warmer microhabitats where specialized creatures congregate.

The increased temperature and chemical richness attract dense communities of tube worms, clams, and microbes. Ocean Exploration Trust documented approximately 500 cold seeps in this region alone.

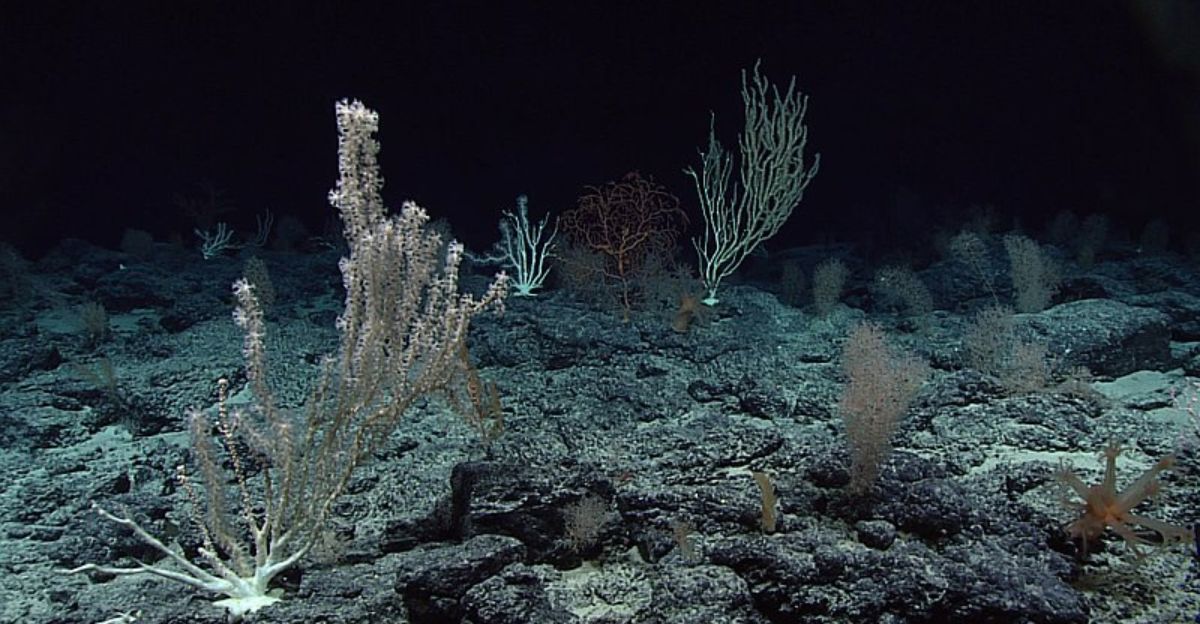

7. Greenland Coral Reefs

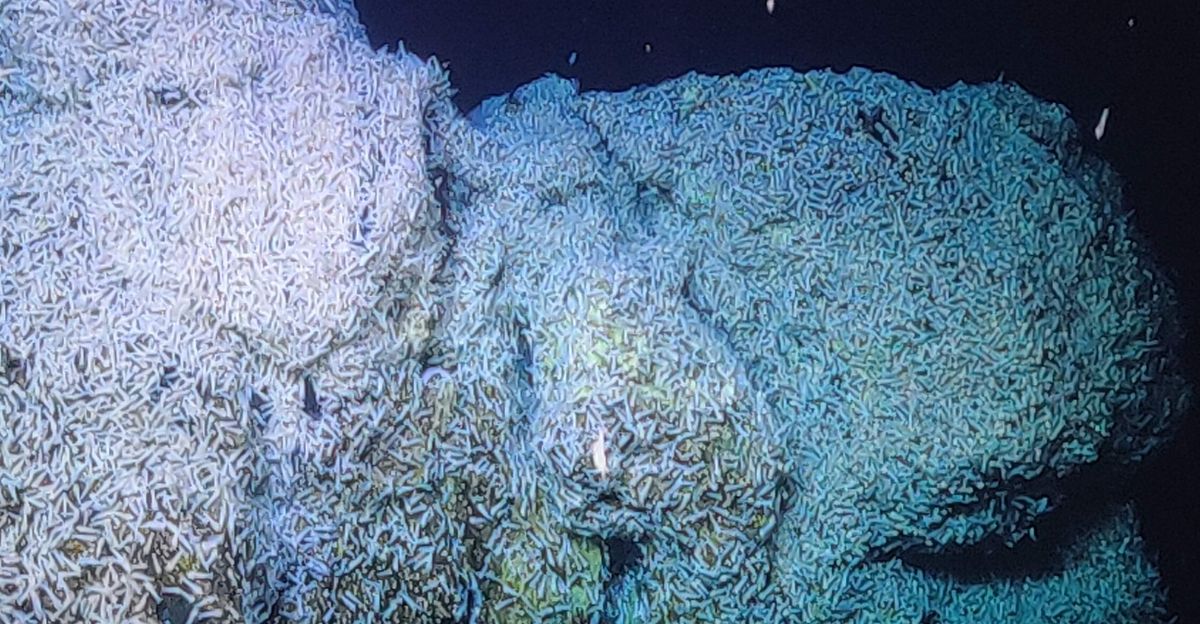

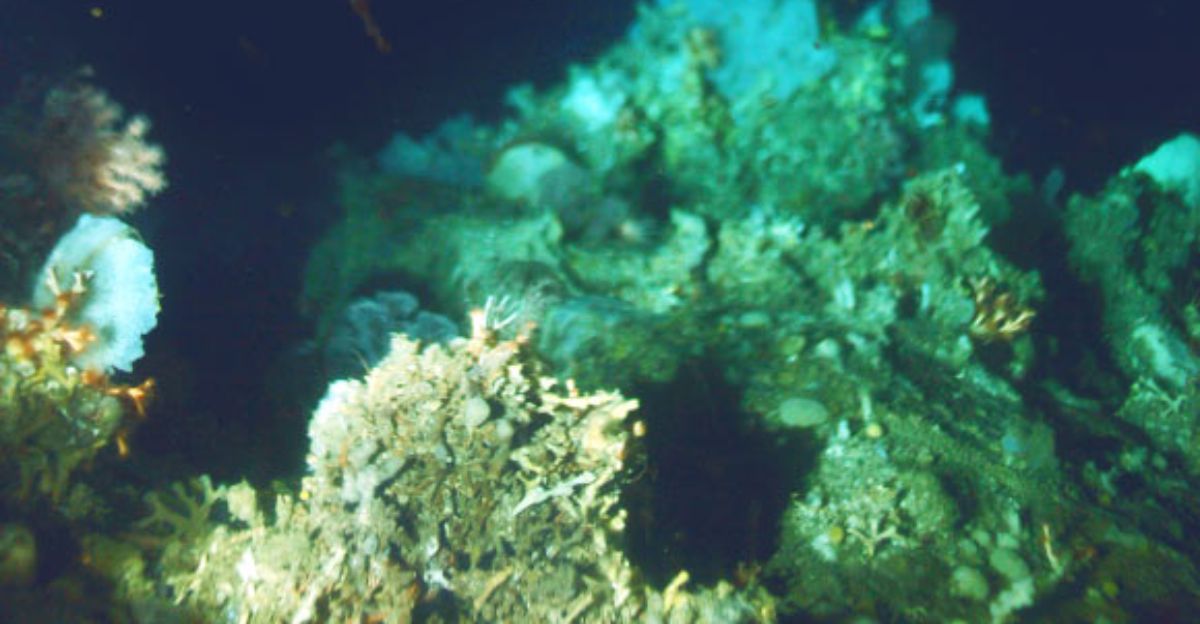

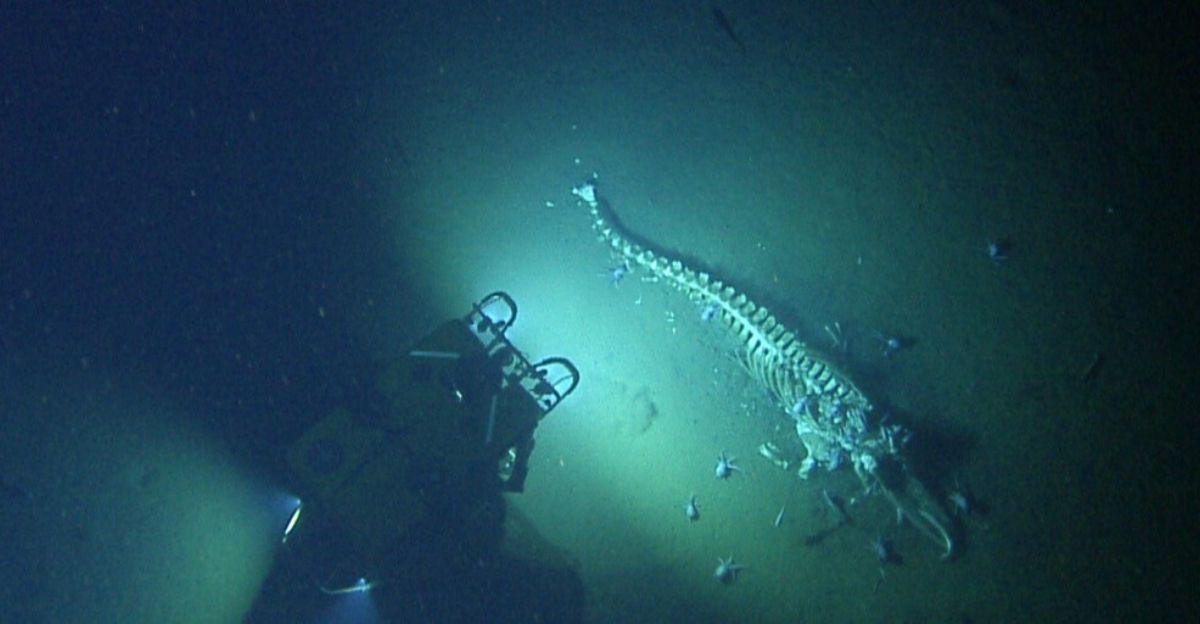

In 2012, scientists conducting deep-sea research 900 meters (about 2,950 feet) below the surface off Cape Desolation on Greenland’s southern coast made an extraordinary discovery by accident.

Their research equipment was damaged by coral structures they hadn’t anticipated—a rare cold-water coral reef.

Unlike tropical corals, which require sunlight, these deep-sea corals derive energy from zooplankton and organic matter sinking from above. The discovery expanded our understanding of where coral ecosystems can thrive.

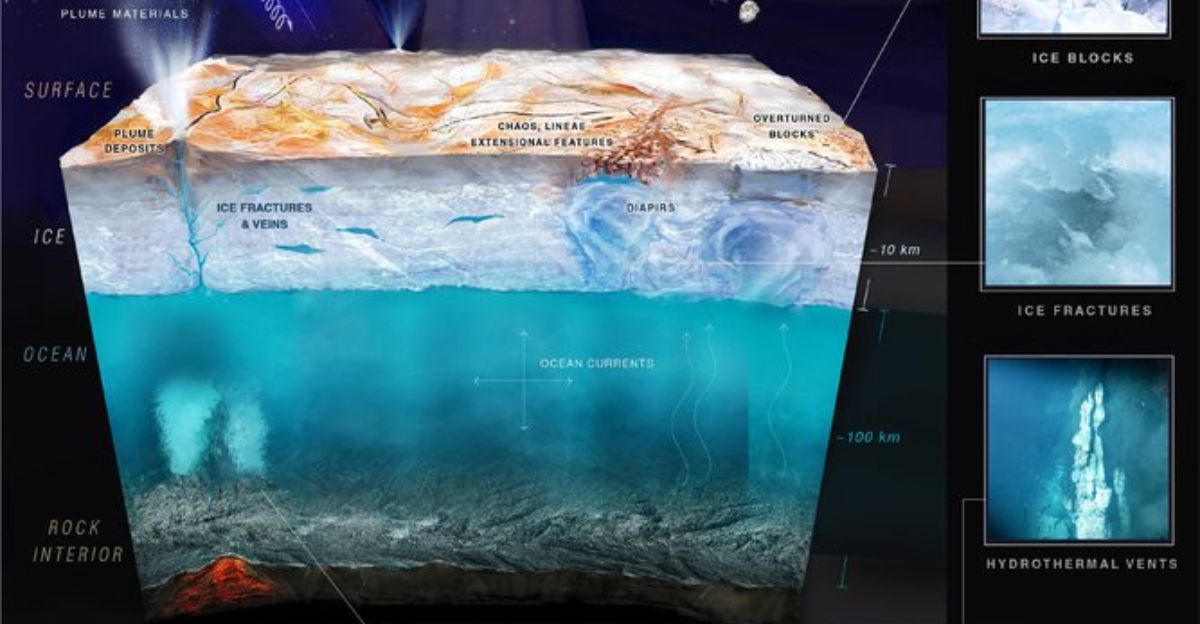

Why Gakkel Ridge Matters to Climate and Life

The Gakkel Ridge’s hydrothermal vents not only support Arctic ecosystems—they play a critical role in Earth’s chemistry and potentially contribute to climate regulation. These vents release minerals, heat, and chemical energy that cycle through the ocean system.

Understanding Arctic vents also helps scientists model the conditions that existed on early Earth and potentially on icy moons like Europa, where similar vent systems might harbor extraterrestrial life. The 2003 discovery opened an entirely new frontier in polar oceanography.

Von Damm’s 500 New Species: Biodiversity Hotspot

When the Von Damm Vent Field was studied, researchers added to a growing tally of around 500 previously unknown animal species discovered at hydrothermal vents along the mid‑ocean ridge system.

This concentration of novelty highlights the limited understanding we have of deep-sea life. Each vent field appears to host unique species adapted to extreme conditions, including near-boiling temperatures, crushing pressure, and the absence of sunlight.

The sheer density of new discoveries suggests that vast tracts of similar seafloor habitat likely harbor equally unique but undiscovered ecosystems.

Cenotes: Sacred Sites and Geological Time Machines

For ancient Maya civilization, cenotes held spiritual and practical significance as water sources. Today, they serve as natural archives of geological history.

Underwater cenotes preserve sediment layers, fossils, and chemical signatures that reveal climate patterns spanning thousands of years.

The Chicxulub impact’s influence on cenote formation demonstrates how a single catastrophic event can profoundly reshape an entire landscape’s hydrology and create unique ecosystems that persist for millions of years.

Silfra’s Plate Tectonics in Real Time

Silfra Fissure is more than a diving destination—it’s a classroom where plate tectonics can be observed directly. The rift grows visibly over human timescales, making it ideal for studying how continental plates separate.

The fissure also highlights Iceland’s unique position as a location where a mid-ocean ridge emerges above sea level, evident in the dramatic landscapes of the island itself.

Water temperature remains stable year-round due to geothermal activity, creating a stable habitat for specialized organisms.

Carter Seamount and the Million-Volcano Mystery

With more than one million submerged volcanoes estimated to exist on Earth’s seafloor, Carter Seamount represents a tiny fraction of studied sites. Most seamounts remain completely unmapped and unstudied, likely harboring unique species and geological features.

Carter’s 2013 study revealed that seamounts function as isolated islands of biodiversity in the deep sea, supporting specialized coral and sponge communities. Each unexplored seamount could rewrite our understanding of deep-sea ecosystems and evolution.

The Cascadia Margin’s Methane Cycle

Champagne seeps release methane accumulated in seafloor sediments over millennia. This methane ultimately originates from the decay of organic matter and microbial processes that occur in anaerobic conditions.

The seeps create chemosynthetic ecosystems where bacteria oxidize methane as an energy source, thereby supporting entire food webs that rely on this process rather than photosynthesis.

Understanding these systems helps scientists model how early Earth’s methane-rich oceans might have supported primitive life before oxygen accumulated in the atmosphere.

Greenland Corals and Climate Change Indicators

Cold-water coral reefs like those off Greenland grow extraordinarily slowly—sometimes only millimeters per year—making them among the longest-lived organisms on Earth.

Their skeletons record chemical signatures of water temperature, salinity, and nutrient levels spanning centuries. As climate change alters Arctic conditions, these corals face unprecedented stress from warming, acidification, and oxygen depletion.

Protecting and studying them is critical for understanding how oceans respond to rapid environmental change.

Technology Making the Invisible Visible

These seven discoveries were only possible due to advances in deep-sea technology, including submersibles, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), and high-resolution sonar mapping.

Equipment that can withstand crushing pressures, near-freezing temperatures, and total darkness now enables the seafloor to be brought into the laboratory.

As technology improves, the rate of underwater discoveries is accelerating—meaning thousands more hidden features likely await detection.

What These Seven Sites Teach Us About Earth

Collectively, these underwater features illustrate that Earth’s seafloor is not a barren desert but a dynamic, biologically rich frontier. They reveal how geology, chemistry, and biology interact in extreme environments.

They show that life thrives in conditions we once thought impossible: near-boiling vents, total darkness, crushing pressure, and methane-rich seeps. Each discovery expands our understanding of where life can exist—both on our planet and potentially beyond it.

The Exploration Paradox: Known Yet Unknown

Ironically, we know more about the moon’s surface than about Earth’s deep ocean floor. Roughly 80 percent of the ocean remains unmapped and unexplored. These seven discoveries represent islands of detailed knowledge in a vast sea of ignorance.

As funding for ocean exploration increases and international interest grows, the rate of discovery is likely to accelerate dramatically in the coming decades, potentially revealing ecosystems and geological features beyond current scientific imagination.

Deep-Sea Conservation and Future Exploration

As interest in deep-sea resources grows—from mineral extraction to pharmaceutical compounds—the imperative to study and protect these fragile ecosystems becomes increasingly urgent.

Cold-water corals, seamount communities, and vent-field organisms evolved in isolation for millions of years. Industrial activities could destroy them before we fully understand their scientific value.

International frameworks for deep-sea conservation are emerging, striking a balance between exploration, protection, and sustainable use.

What Lies Below: The Next Frontier

These seven underwater discoveries are just the beginning. Thousands of seamounts, tens of thousands of hydrothermal vents, and countless unmapped geological features await exploration.

Each one potentially harbors new species, new chemical processes, and new insights into how Earth works.

The ocean floor is humanity’s last great frontier. In this place, scientific discovery remains as exciting and consequential as any space mission, yet far more accessible and immediately relevant to understanding our own planet.

Sources:

BBC Science Focus – Von Damm Vent Field and hydrothermal vent research

Ocean Exploration Trust – Champagne Seeps and Cold Seeps Discovery Reports

University of Bristol – 2013 Carter Seamount study

Chicxulub impact research – Cenotes geological formation studies

Icelandic geological surveys – Silfra Fissure plate tectonics documentation

2003 Arctic hydrothermal vent discovery – Gakkel Ridge research archives