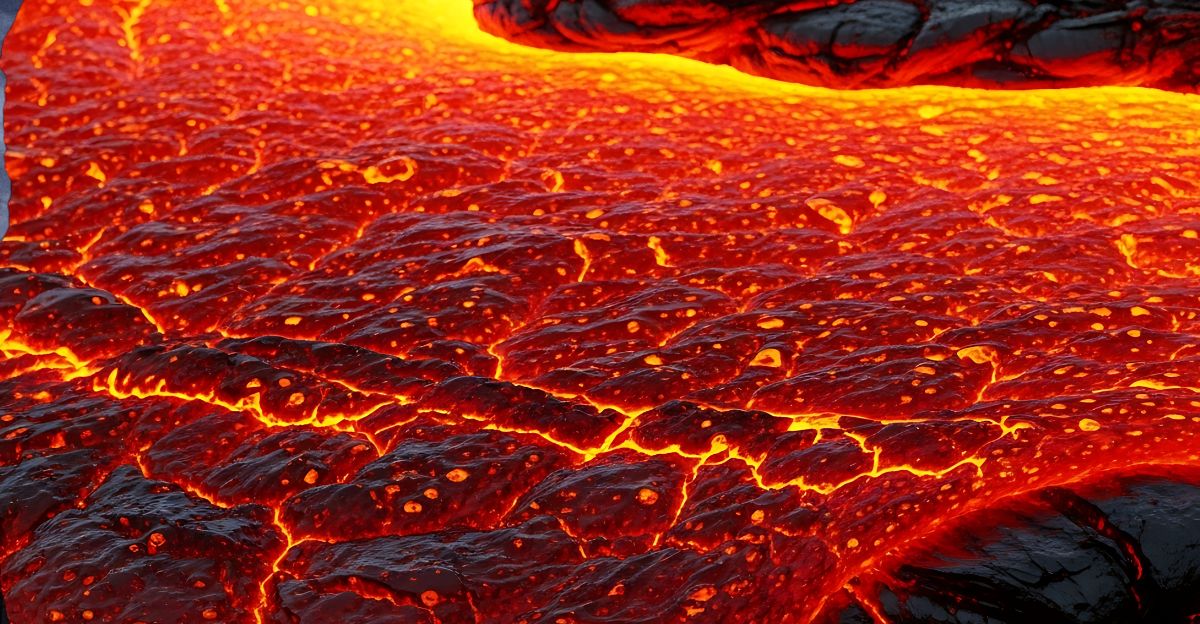

The ground trembles, the air thick with smoke—then, a violent eruption, sending clouds of ash billowing miles into the sky. This isn’t some distant possibility—it’s a terrifying reality waiting beneath the surface.

Yellowstone’s supervolcano, with its catastrophic power, has erupted three times in the last 2.1 million years. If it erupts again, entire towns in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho will vanish in a matter of hours.

Pyroclastic flows, faster than a hurricane, will swallow everything in their path, while ash rains down, hot enough to incinerate everything it touches. What would be left? Scientists have pinpointed the very communities that would face total destruction. But this is just the beginning of the story.

1. West Yellowstone, Montana

This gateway town of roughly 1,300 residents sits just a few miles from the caldera’s western edge, placing it squarely in FEMA’s designated “Zone One”—the area most likely to be affected by the unsurvivable impact.

If Yellowstone erupts, West Yellowstone would be obliterated within minutes by pyroclastic flows exceeding 752°F, traveling at speeds exceeding 186 miles per hour. The FEMA assessment estimates 70,000 people live in Zone One, where survival is impossible.

Buildings, roads, and infrastructure would be buried under up to three meters of superheated volcanic ash and debris, erasing the town from existence before most residents could even attempt evacuation.

2. Mammoth Hot Springs, Wyoming

Located inside Yellowstone National Park itself, Mammoth Hot Springs serves as the park headquarters and houses hundreds of employees and visitors year-round. It’s the second major population center specifically named in FEMA’s Zone One classification.

The community sits directly atop the volcanic system, making it ground zero for catastrophic pyroclastic density currents that would incinerate everything in seconds.

No warning system could provide sufficient time for evacuation. The iconic thermal terraces that attract tourists would become the epicenter of destruction as superheated gases and volcanic debris sweep across the landscape at jet-engine speeds.

3. Gardiner, Montana

Just three miles from Yellowstone’s northern boundary, Gardiner’s 900 residents live in the immediate blast shadow of the supervolcano.

This historic gateway community, famous as the original entrance to America’s first national park, would be engulfed by the initial pyroclastic surge. Earthquake swarms regularly rattle Gardiner as magma shifts beneath the surface, serving as constant reminders of the volcanic threat.

The town’s proximity means it would experience the eruption’s full fury—superheated gas clouds, ash flows, and complete infrastructure collapse—within the first critical minutes when survival chances drop to zero.

4. Livingston, Montana

About 50 miles northwest of Yellowstone, Livingston’s 7,500 residents might assume distance provides safety. They’d be wrong. Scientific modeling shows pyroclastic flows from a supereruption could race across the Montana countryside and engulf Livingston within one hour of the initial blast.

These deadly currents—mixtures of gas, ash, and rock fragments—can travel over 62 miles from the source, maintaining lethal temperatures above 392°F.

The town’s valley location offers no protection; historical eruptions demonstrate that pyroclastic flows follow terrain, channeling through valleys with devastating efficiency. Livingston would face complete destruction before emergency services could mobilize a meaningful evacuation.

5. Jackson Hole, Wyoming

The scenic Jackson Hole valley, home to 10,000 year-round residents and world-famous ski resorts, sits approximately 62 miles south of the caldera.

Despite being a separate geographic basin, scientific models predict that pyroclastic flows would “race across the countryside and engulf the valley of Jackson Hole” within the first hours of the eruption.

The valley’s tourism-dependent economy and luxury real estate market—with property values exceeding billions—would be completely wiped out. Teton County emergency management acknowledges the volcano threat but admits evacuation planning faces insurmountable challenges given the speed and scale of potential pyroclastic surges that respect no geographic boundaries.

6. Billings, Montana

Montana’s largest city, with 117,000 residents, sits 109 miles from Yellowstone—far enough to escape pyroclastic flows, but positioned directly in the primary ashfall trajectory. Researchers now estimate Billings would be buried under over 4.5 feet of volcanic ash within 24-48 hours of eruption.

This depth would collapse most roofs, bury vehicles, contaminate all water supplies, and create a cement-like mixture when combined with moisture.

The 2014 USGS study specifically identifies Billings as one of the cities in greatest danger from ashfall, facing infrastructure paralysis, mass casualties from building collapses, and a complete economic shutdown lasting years or permanently.

7. Casper, Wyoming

Casper’s 59,000 residents live 155 miles southeast of Yellowstone, yet scientific modeling places the city in the extreme danger zone for catastrophic ash burial. The USGS 2014 supereruption study concluded that “Billings and Casper are covered by tens of centimetres to more than a metre of ash”—meaning up to 4 feet of volcanic debris.

Multiple sources confirm Casper would be “buried under more than a meter of ash,” rendering the city completely uninhabitable.

Buildings would collapse under the weight, all transportation networks would cease functioning, and the ash would form a concrete-like consistency in the lungs, causing mass suffocation. The city’s oil refining infrastructure would fail catastrophically, creating secondary industrial disasters.

8. Boise, Idaho

Idaho’s capital and largest city, home to 240,000 people, sits approximately 217 miles west of Yellowstone. While outside the pyroclastic flow zone, Boise falls within the heavy ashfall corridor that would receive “at least several inches of ash and as much as 11 inches” according to 2014 USGS modeling.

Even the lower estimate—several inches—would shut down the city entirely. Aircraft couldn’t fly through ash clouds, cars would stall as ash clogs engines, electrical grids would fail from contamination, and water treatment plants would be overwhelmed.

Eleven inches of ash weigh approximately 100 pounds per square foot, collapsing many structures and creating uninhabitable conditions that require potential permanent evacuation.

9. Salt Lake City, Utah

Utah’s capital, with 200,000 residents (1.2 million in the metro area), sits 236 miles south of Yellowstone, along prevailing wind patterns. Scientific modeling indicates ashfall “could be deeper than 3 feet” in Salt Lake City within 24-48 hours of eruption.

Three feet of volcanic ash would bury first-floor windows, make all roads impassable, collapse most commercial buildings, and create apocalyptic conditions across the Wasatch Front. The city’s bowl-like valley geography would trap ash, concentrating accumulation.

Mormon Temple archives, government facilities, and cultural institutions would face burial or catastrophic damage. The University of Utah’s seismologists have studied Yellowstone extensively, acknowledging their own city faces an existential threat from ash inundation.

10. Denver, Colorado

Colorado’s capital, home to 715,000 people (2.9 million in the metro area), sits 515 miles east-southeast of Yellowstone—yet remains firmly in the disaster zone.

Multiple sources confirm that Denver would receive “at least several inches of ash and as much as 11 inches,” with one model suggesting that the accumulation “could be deeper than 3 feet” depending on wind patterns.

Ash would reach Denver within 24 hours of the eruption, shutting down Denver International Airport, collapsing buildings across the metro area, and contaminating the water supplies of Cherry Creek and the South Platte River. The city’s elevation and eastern slope position make it particularly vulnerable to ash carried by prevailing westerly winds across the Rockies.

The 90% Kill Zone

Within 621 miles of a Yellowstone supereruption, scientists estimate a staggering 90% fatality rate—potentially 78 million Americans based on current population distribution.

This “kill zone” extends far beyond the immediate pyroclastic flow radius, encompassing deaths from ashfall suffocation, building collapse, contaminated water, and infrastructure failure. The ash would form a cement-like mixture in victims’ lungs, causing mass suffocation across multiple states.

FEMA’s 2015 assessment warned that direct economic damages could reach $3 trillion—approximately 20% of U.S. GDP—with recovery taking decades or proving impossible for the hardest-hit regions.

Ash Becomes Concrete

One of Yellowstone’s most horrifying dangers isn’t the initial blast—it’s what the ash does to human lungs. When volcanic ash mixes with moisture in respiratory systems, it forms a concrete-like substance that suffocates victims.

The microscopic glass shards that comprise volcanic ash are small enough to penetrate deep into the lungs but cannot be coughed out. Across the western United States, millions would die not from heat or impact, but from slow suffocation as their lungs filled with hardening ash-cement.

Even survivors wearing basic dust masks would face silicosis and permanent lung damage. Medical systems would be overwhelmed within hours, with no treatment available for mass ash inhalation casualties.

Three Supereruptions in History

Yellowstone has experienced three massive supereruptions over the past 2.1 million years—geological events that ejected more than 250 cubic miles of debris each.

The Huckleberry Ridge eruption (2.1 million years ago) was the largest; the Mesa Falls eruption occurred 1.3 million years ago, and the most recent Lava Creek eruption happened 640,000 years ago, creating the current caldera.

Each eruption ejected between 149 and 621 cubic kilometers of material, burying much of North America under a layer of ash.

The roughly 660,000-year interval between eruptions has led some to speculate that another is “overdue,” though USGS scientists emphasize that volcanic systems don’t follow predictable schedules and the current magma chamber shows no signs of an imminent eruption.

No Warning Possible

The terrifying reality of Yellowstone is that certain eruption types—particularly hydrothermal explosions—can occur “with no warning,” according to USGS scientists. While continuous monitoring tracks earthquakes, ground deformation, and gas emissions, researchers admit they’re “not completely sure when” a major eruption might occur.

The magma chamber sits 3-6 miles below the surface, making direct observation impossible. Past eruptions occurred without the kind of sustained precursor activity that allows evacuation planning.

Even if warnings came days in advance, evacuating millions from a multi-state region would prove logistically impossible. The 70,000 people in Zone One would have no survivable options once the eruption begins.

Continental Ash Coverage

The 2014 USGS computer modeling study mapped ash distribution across North America, revealing that three-quarters of the United States would receive measurable ashfall from a Yellowstone supereruption.

Cities as far as Minneapolis and Des Moines would receive centimeters of ash—enough to ground all aircraft, contaminate water supplies, and disrupt power grids. The ash cloud would spread coast-to-coast within days, with prevailing westerly winds pushing the heaviest concentrations eastward.

Even a few millimeters of ash causes catastrophic problems: it’s abrasive enough to destroy jet engines, conductive enough to short-circuit electrical systems, and heavy enough when accumulated to collapse buildings. NASA estimates over one million square miles could be covered.

Global Climate Catastrophe

Beyond immediate destruction, a Yellowstone supereruption would inject massive volumes of sulfur dioxide and volcanic aerosols into the stratosphere, triggering global climate disruption. Historical supereruptions caused “volcanic winters” that lasted for years, with global temperatures dropping by several degrees Fahrenheit.

The 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora—far more minor than a Yellowstone supereruption—caused the “Year Without a Summer” in 1816, resulting in widespread crop failures and famine across Europe and North America.

A Yellowstone event would be 10-100 times larger, potentially disrupting growing seasons worldwide for a decade. Food production would collapse, triggering mass starvation, economic depression, and geopolitical instability as nations compete for dwindling agricultural resources.

Mostly Solid Magma Chamber

Despite catastrophic potential, current scientific monitoring provides reassurance: the Yellowstone magma chamber is “mostly solid” according to USGS assessments. Seismic imaging reveals that only 5-15% of the chamber contains molten rock—far below the 50%+ melt fraction required for supereruption.

The November 2025 USGS Yellowstone Volcano Observatory monthly update confirms “Yellowstone Caldera activity remains at background levels” with the current volcano alert level at NORMAL and aviation color code GREEN.

While earthquake swarms and ground deformation occur regularly, these represent normal activity for an active volcanic system, not precursors to imminent eruption. Scientists emphasize the magma chamber would need centuries of recharging before supereruption becomes possible.

Lava Flows More Likely Than Supereruption

The most probable volcanic activity at Yellowstone isn’t a civilization-ending supereruption, but rather lava flows similar to those of the most recent eruptions 70,000 years ago. Of Yellowstone’s past 23 volcanic events, 20 were lava flows that produced minimal ash and no catastrophic regional impacts.

USGS scientists state that “the next eruption will likely be a lava flow, not a supereruption,” with hydrothermal explosions representing the most realistic near-term threat.

These steam-driven blasts occur when superheated water suddenly vaporizes, creating craters hundreds of feet across—dangerous to nearby visitors but not existential threats. The annual probability of a supereruption remains extraordinarily low: approximately 1 in 730,000, or 0.00014% per year.

Monitoring the Sleeping Giant

The USGS Yellowstone Volcano Observatory operates one of the most sophisticated volcano monitoring systems on Earth, with networks of seismometers, GPS stations, stream gauges, and satellite imagery providing real-time data on the caldera’s behavior.

Scientists track thousands of small earthquakes annually, measure ground deformation with millimeter precision, and analyze gas emissions from thermal features. This vigilance ensures that if the magma chamber begins recharging toward supereruption—a process that requires centuries—scientists can detect changes decades in advance.

While the specific locations identified would face catastrophic impacts if Yellowstone were to erupt, current evidence suggests that humanity has considerable time before facing this existential geological threat. The supervolcano sleeps, monitored but not immediately menacing.